Resilience and Resistance at Angel Island: In Conversation with Tomie Arai

While in Residence at Headlands in Fall of 2019, McLaughlin Awardee Tomie Arai was engaged in a number of projects, collaborations, and areas of research. One such area revolved around Angel Island, a 1.2-square-mile island in the San Francisco Bay with a history as layered and dense as the sedimentary stone that forms its geology. Tomie’s interest in the site predates her Residency at Headlands by a number of years: in 2014 she was commissioned to design a series of architectural glass murals for a BART station being built in San Francisco’ Chinatown, and her research for that project led her straight to Angel Island: an historic port of entry for immigrants to the US. While at Headlands, Tomie was surprised to learn that, despite its proximity, many Headlands artists, staff, and guests had never visited Angel Island. Tomie began the process of developing a dedicated shelf in the Headlands Library—a resource for our Artists—to house a collection of works about the history of the island.

In late 2019 and early 2020 we followed up with Tomie to learn a bit more about how this project intersects with her ongoing work and community organizing. Though our exchange took place prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, her thinking on history, trauma, and dislocation, remain intensely relevant.

HCA: Did you come to Headlands with this area of research or interest in mind, or did it emerge once you were here?

Tomie Arai: Every Asian family living in the US has an immigration story and, like many of the thousands of Asian immigrants to travel to California in the early part of the 20th century, my family’s story began at Angel Island. My grandmother was a picture bride from Japan who was allowed to immigrate to America under the US-Japan Gentlemen’s Agreement in 1914. She was processed and detained at the Angel Island detention center for many months; when she was finally released, she met and married my grandfather in San Francisco.

Angel Island State Park is a California Historical Landmark located in the San Francisco Bay, only two miles off the shore of the Marin Headlands. Formerly the home of the Coast Miwok Indians, Angel Island was the site of a detention facility that once processed over 1 million immigrants crossing over the Pacific Ocean. From 1910 to 1950, the Angel Island Immigration Station functioned as the West Coast equivalent of Ellis Island, although the Angel Island facility enforced policies designed to exclude, rather than welcome, immigrants arriving to the US. The primary purpose of the station was to investigate Chinese who had been denied entry because of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882—the act was officially repealed in 1943—but the Detention Center was also used to inspect and detain immigrants from over 84 different countries in Europe, Asia, and the Pacific Rim.

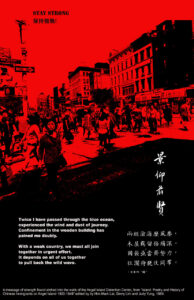

In 1970, the site was slated for demolition because of its deteriorated condition; the discovery of Chinese poetry that had been carved into the walls of the detention barracks saved it from destruction and led to a renewed interest in the Angel Island Immigration Station. Over 135 poems written by Chinese who were confined for months while awaiting release were etched into the walls of holding cells, forming a collective record of the difficult voyage to America and the humiliating treatment many detainees experienced upon their arrival on US shores. More importantly, the discovery of these poems increased public awareness of the immigration experience and the significance of this site and its special history. In honor of this cultural legacy, a Poetry in Parks Festival is held annually on Angel Island. During my residency in October [2019, the] poetry festival featured Headlands Affiliate Shelley Wong.

How do you connect these resources on Angel Island to other work you were engaged in while in residence, and to your broader ongoing work independently and with Chinatown Art Brigade?

Back in New York, I am a co-founder of the Chinatown Art Brigade, a cultural collective of Asian American and Asian diasporic artists and activists who have facilitated a series of community led responses to gentrification and displacement. We have organized town halls, direct actions, and cultural projects that honor local histories and mobilize Chinatown residents to protect and preserve the spaces they live and work in.

As an artist born and raised in New York, and as a recipient of the first McLaughlin Award for Social Practice, coming to the Headlands was an opportunity to reflect on my social practice and a lifetime of working in urban communities. Headlands is breathtakingly beautiful and I expected to use my residency as a retreat—I did not expect to find multiple points of connection between my work in NY Chinatown and my visit to Marin—between the evictions and lack of affordable housing that are threatening immigrant families in the city where I live and the power outages and devastating wildfires that are threatening the way of life across California. Experiencing this environmental crisis first-hand challenged me to question how displacement, climate change, immigration, and cultural activism are interrelated and I asked myself how I could link these connecting threads together in my work and my practice. It was clear to me that no matter where you are, the terrible loss of a home or a place embedded with memory is a shared trauma and living with the fear and anxiety of displacement has an immeasurable, collective impact. Sometimes it takes an out-of-control wildfire or a state-wide power outage to see how important it is to identify what we most care about in our lives and what we can do to fight for the people and places most at risk.

Today, we face a different but equally devastating calamity at our national borders: a human rights crisis and a dysfunctional immigration policy that is at a breaking point. In addition to the books on the shelf, there are resources online and in print about the history of immigration to the US and the history of the Indigeous peoples who were the original stewards of this land. I would urge everyone to learn more about these shared histories and I would also encourage the Headlands staff and residents to visit Angel Island and experience the power and beauty of the place itself. As a historic landmark intimately tied to the history of the Headlands and the Bay Area, Angel Island is a symbol of resilience and resistance that we can all draw some hope from.

Tomie, and Headlands, would like to acknowledge the life and work of Judy Yung, who sadly passed on December 14 of last year. Judy was born and raised in San Francisco Chinatown, and was the daughter of immigrant parents detained at Angel Island. Her professional accomplishments are many, and include her groundbreaking work on documenting the histories of the Angel Island Immigration Station.